A Conversation with OMGidrawedit

Building Folklore Out of Pixels

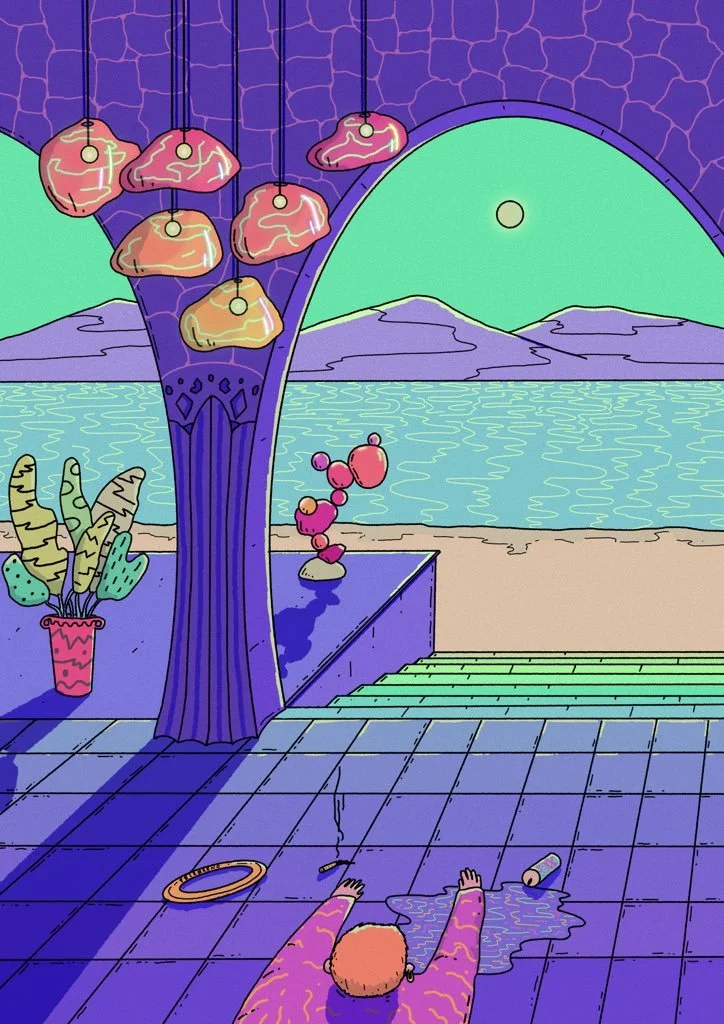

To look at an illustration by OMGidrawedit is to enter a dense ecosystem: bright colours, surreal characters, and layers of detail that feel equal parts comic panel, folk tale, and fever dream. It’s tempting to call this world-building, but as the Exeter-based artist admits, he’s still figuring out what that really means for himself.

“I hurt my wrist about a year ago and couldn’t do my usual style,” he tells me. “That’s when I started experimenting with looser pieces, even painting landscapes inside video games. I’d float the camera around and think about the graphics. The N64 was the console I grew up with. The graphics were never as good as my memory imagined them.”

This tension, between memory and imagination, between technology and nature—runs through his practice.

One Knee Two Knee

Beginnings and Identity

At university, his drawings were “really bad,” as he puts it, but a professor encouraged him to push through. “Some students are quite shit at drawing,” the professor said, “but you have something, so don’t lose it.” From there, he developed his signature dense, almost folkloric style.

A commission forced him into colour: “My work had been so monochrome and detailed that colour seemed daunting. A musician asked for colourful merch, and that was the push.”

More recently, he’s discovered he has aphantasia: the inability to picture things in the mind’s eye. “I can’t close my eyes and see an apple, but I know an apple,” he explains. “So where are these visual ideas coming from? A lot of it is self-talk more than imagery. Meditation helps. In that border between sleep and waking, I sometimes glimpse visuals. That’s where stories come from, where the door opens.”

What emerges on the page, then, is often the first time he actually “sees” his ideas: referenceless yet overflowing with narrative.

Process and Craft

Working digitally, he starts with a rough sketch—a mess, by his own description—then redraws and cleans it up in layers. “The rough stage is the most time consuming. Hours of pencil drawing, and then I build on top of that. It’s like construction and deconstruction at once.”

The process is a kind of storytelling in itself: “When I’m in the flow, it’s like storytime in my head. I invent lore for each object and element as I draw.”

Knowing when to stop is harder. “I don’t think a piece is ever truly finished. I look at older works and think, I wish I’d added more. But I try to see each piece as capturing a moment in time. I stop when the composition feels balanced, when the colours work, when I feel I’ve told enough of the story for now.”

Recipes for Disaster

Humour, coping and themes

At first glance, his work is playful—even cute—but beneath the surface run themes of anxiety, memory, and environmental crisis. Humor, he explains, is both instinctive and intentional.

“I’ve always used humour as a coping mechanism. I’m that person who makes the joke at the worst—or best—possible time. So it naturally seeps into the art. People say art should be serious, but why can’t you feel joy from it?”

The pandemic years sharpened this dynamic. After releasing one of the first PFP projects on Tezos, he found himself targeted by online criticism. “Everything fell back on one creator. It was overwhelming.” Meditation, again, became a refuge. He cites Dalí’s key-in-hand trick—staying on the cusp of sleep to access dreamlike imagery—as a method he also experiments with.

People of Tezos

Nature, Memory, and Sci-Fi

Though chronically online, he insists on going outside: “The touch grass meme is very real. Nature resets me.” His work often reflects this longing for reconnection—slowing down, remembering video stores and split-screen games as much as forests or oceans.

Science fiction sits alongside these natural influences. “Growing up in the late 80s, tech and sci-fi felt magical. The tension between them and nature just became part of my practice. Sometimes I weave them together, sometimes I set them against each other.”

Worlds Shared, Worlds Expanded

Digital sharing is both lifeline and risk. “It’s essential for my career, but also creates new layers of meaning. People reflect on my work and trigger memories of my own. Sometimes they miss the point completely—but that’s part of the art.”

Ultimately, what he hopes viewers find is recognition:

“I love how my work opens a window through shared memories. Even though the imagery is fantastical, there’s a lot of reality in it. People see their own version of the story, and that’s where the real connection happens. What I hope most is that it sparks that feeling of I know this, I’ve been there. And maybe, it encourages someone to look deeper into my world.”